I wrote this piece way back in 2014, for LitReactor. I’m sharing it now because I’ve just learned that Tom has passed away. Tom’s work meant the world to me, and not a week goes by that I don’t refer to one of his books, or one of the writing lessons I learned from him—many of which I’ve adapted into my own teaching.

He is one of the great writers, and I while I would never claim to be in the same class as him—I don’t know many writers who are—his artistic DNA is mixed deeply and indelibly with mine. The weekend I spent in a workshop in his basement in Portland was one of the most formative weekends of my life, made all the more special because it’s where I met , who I know walked away just as struck as I was.

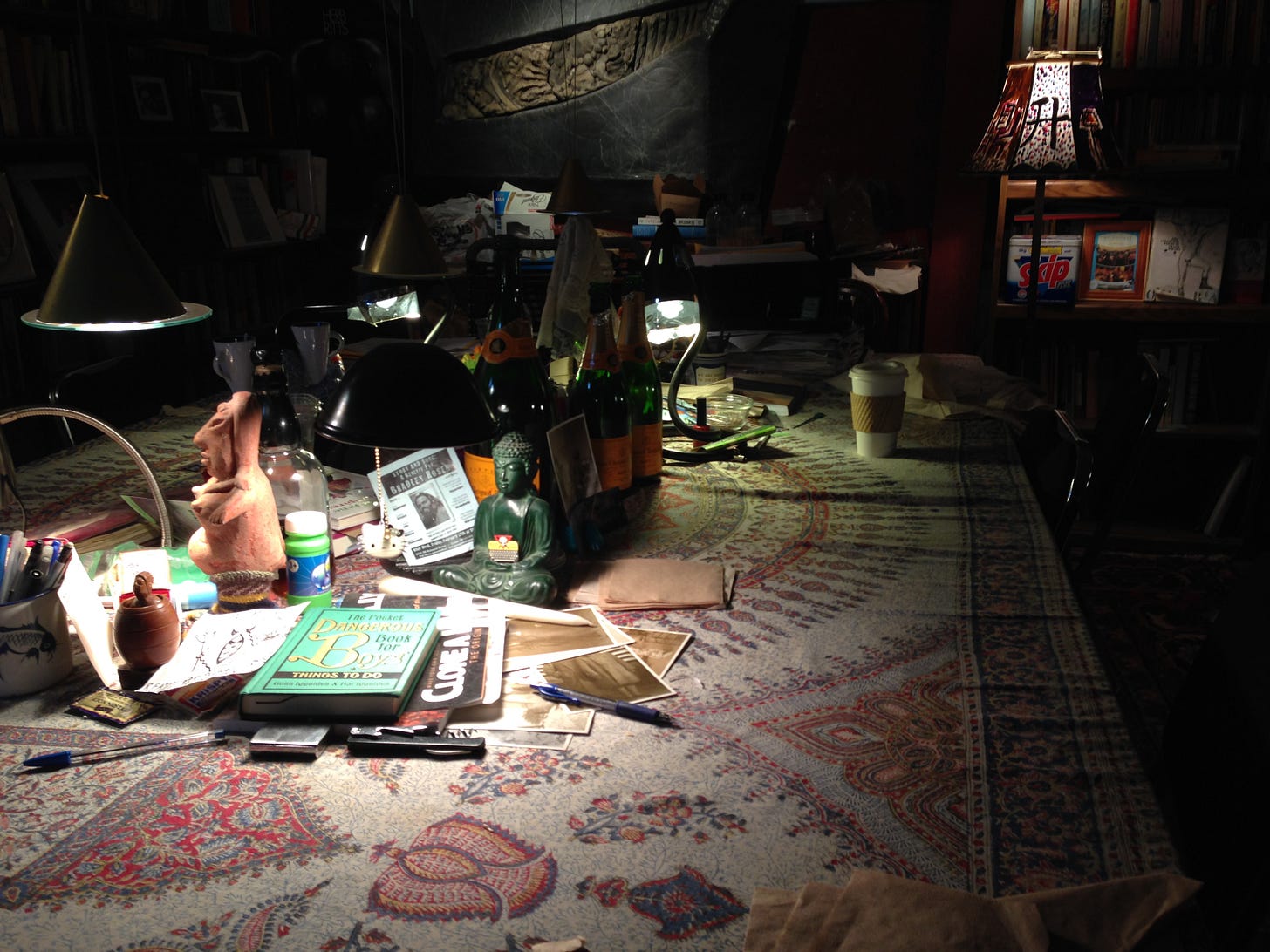

Ever since that workshop, the wallpaper of my computer—every computer I’ve owned since then—has been a picture I took of the table where we all sat, one morning before we got started. It’s full of talismans and artifacts of writers who came before me. It’s my understanding that was the last in-person workshop he taught, and I am beyond lucky to have had that experience.

I look at the picture every time I write. It reminds me of the places I need to go to, and what I need to carry with me.

I've been planning to write this for months, and I've done everything I could to put it off. The reason for that is because I am afraid to write it. No matter what I write, I'll never get across the thing about Tom Spanbauer's writing that touches me so deeply.

The sensation of reading his books is that, while you're reading them, it's like he's placed his hand on your chest, the warmth and pressure and intimacy of it reassuring you that you are alive, and you are not alone.

That doesn't cut it. It gets close, but it's not there. The best I can do is approximate.

Even scarier is the idea that Tom may read this, and then I'll see him, and then what do I do? I have to look him in the eye after I've admitted these things. That his work is my gold standard; what I hope to be, and what I know I'll never achieve. That reading The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon during my formative years challenged and informed my ideas of what love means.

Writing these things here, at least, I don't have to say them aloud to him, or to anyone else.

Tom founded Dangerous Writing, which is about going to the place that hurts, overcoming your fear, and writing the truth. I was fortunate enough to take that class, three days in the basement of his home in Portland last November. So I have to tell the truth right now. Anything else would be cheating.

And the truth is that I fucking love Tom Spanbauer. I feel like I'm a better person for having read his books. Not just a better writer. A better person.

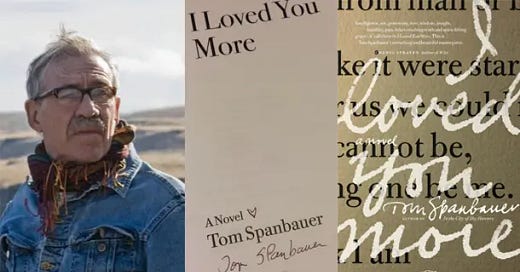

His fifth novel, I Loved You More, comes out this week from Hawthorne Books, and I knew I wanted to review it for the site. But I also couldn't just write a review, because that's too small. Also, I hate reviews. Literary criticism is something I've never really understood, and most of the time it's bullshit anyway. The scope of a review is too small for something like this.

Here are facts about Tom. Worth putting up front:

He grew up on a farm outside Pocatello, Idaho. He served two years in the Peace Corps in Kenya, and lived in New Hampshire, then Vermont, then Key West, Florida. In 1988, he received his MFA from Columbia University in New York City, where he studied under Gordon Lish. In 1991, Tom settled in Portland, Oregon, where he teaches Dangerous Writing. Tom's writing explores issues of race, family, and sexual identity. Tom is gay and was diagnosed with AIDS in 1996, his illness being another recurring theme in his books. Many of his students have gone on to publish their work to high acclaim, including Chuck Palahniuk, Suzy Vitello, Monica Drake, and Stevan Allred.

Those are the facts. Worth knowing, but not the whole truth. The truth of Tom is in his books, and even though I Loved You More is what I'm supposed to be talking about, it makes more sense to start at the beginning.

As Tom told us during the Dangerous Writing workshop: Fiction is the lie that tells the truth truer.

Faraway Places (1989)

He walked over to me, but I wasn't afraid. He couldn't hurt me anymore.

But he did. My father hurt me again.

My father just walked over and put his arms around me, just walked up to me—no problem—after all those years and grabbed onto my neck and hugged me, hugged me because he needed it. Maybe because he thought I needed it too.

Faraway Places is a slim volume—more a novella than a novel. Set in 1950s Idaho, it follows 13-year-old Jake Weber, who witnesses the murder of a Native American woman by a town banker. The woman's African American lover is falsely accused of the crime, but Jake's parents swear him to secrecy.

The writing is stripped down, almost sparse, but at the same time vivid, and it touches on some of the themes that will come to resonate through Tom's books: Native American culture, the rift between father and son, the things that are kept hidden, and the walls that are built to hide them.

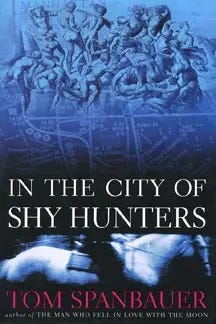

It was interesting to revisit this recently; In the City of Shy Hunters, Now is the Hour, and I Loved You More feel so biographical. This is the most straightforward of all of Tom's books, without the doses of magical realism that he would go on to use as a storytelling device. Still, you can see parts of Tom roiling beneath the surface—signs of the choruses that would come to repeat through his writing.

The biggest theme, the one that Tom does so well, is the moment of change. Jake's regimented, church-on-Sunday life is upended. Everything after this is different. He knows he's at a point in his life where there's something that's next, he's just not exactly sure what that next thing is. It's not a spoiler to say the book ends with him leaving the farm.

Leaving that farm feels like a gateway that needed to be passed, so the rest of these stories could be told.

The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon (1991)

"The best stories," Dellwood is always telling Shed, "are the true stories."

Shed is a half-Indian bisexual boy who lives and works at the Indian Head Hotel in the tiny town of Excellent, Idaho, at the turn of the century. He makes his home with a surrogate family—proprietress Ida Richilieu, mad cowboy Dellwood Barker, tempestuous prostitute Alma Hatch—while seeking the truth of himself and the world around him.

This is the first book of Tom's that I read. This is going back a long time—more than a decade. It's also the most removed from reality. This is a fairy tale, rooted in Native American tradition, much of it based on Tom's friendship with a two-spirit Shoshone-Métis. It is, at times, incredibly brutal. Shed, as a child, is raped by the villainous Billy Blizzard. A woman's legs are amputated. A lot of people die.

But there's also a startling beauty on display, in the vistas of the Old West, and in the hearts of the characters. And I mean it, when I say that this book challenged my ideas of what love means.

This book was the first of its kind I ever read where love exists in a spiritual state, given definition by the people around you. Where two men loving each other is tender and thoughtful. Not a joke, or something to be afraid of. Where the world is a big scary place that's full of hope if you know where to look for it.

In the City of Shy Hunters (2001)

New York is America's charcoal heart. New York burns out all the extra stuff in your life. You have to be able to state what you want and why you want it as precisely and concisely as possible. There's no time for anything else. Life is an art and art is a game, Fiona said. I see that you are playing at enjoying your Szechuan Chicken, Fiona said.

Will Parker, a shy boy from Idaho, moves to New York City during the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. He falls in love with a six-foot-five African-American drag queen and performance artist named Rose, and watches as the city thrashes and convulses around him.

It might be my favorite book. That's a tough declaration to make. But it might be.

It's not always easy to find art that conveys an authentic face of New York. More people fail than succeed. Shy Hunters, though, surpasses even the best attempts and gets down to New York's charcoal heart. There's a cadence to this that's just so perfect. The way Tom understands how the people and the streets fit together. Like it's a puzzle and he's figured it out. He finds the beauty under the layers of crud and anger and fear, under the protective armor that New Yorkers put up, and offers a level of insight that's nearly a historical narrative of the Bad Old Days of the 80s. A time that people my age know only through stories, so it's practically legend anyway.

And as with The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon, the story is about Will, but also his surrogate family. The people we surround ourselves with when our real families fail us. And it's about Will growing up in Idaho, and searching for Charlie Two Moons, his blood brother and first lover. It's an amalgam of all these things that we've come to know about Tom's work at this point, threading that needle between Faraway Places and The Man Who Fell in Love with the Moon. This one is still marked with some magical realism—beautiful, in its execution—but this is the first time in Tom's bibliography that you feel like you're standing in a worn, comfortable pair of his shoes.

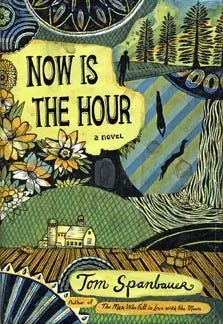

Now is the Hour (2007)

All around me there were tulips. Planted in the borders along the porch with the columns and along the wide cement sidewalk into the entrance, red tulips, yellow tulips, pink tulips.

How can it be so beautiful while you are so afraid?

It's 1967, and Rigby John Klusener is 17, finally leaving his family's farm in Idaho, headed to San Francisco. The book starts with him on the side of the road, his thumb stuck up in the air, and then brings us full circle, from his childhood, to what brought him there. Ribgy John is Jake Weber, telling the bigger truth about his life. Ribgy John is Will Parker, before Will showed up in New York City.

One of Tom's greatest skills as a writer is that he'll drop a detail in the beginning of a narrative—here it's that someone is sitting at the kitchen table when Rigby John is leaving the house for good—and circles back to it in a way that makes it surprising and inevitable and resonant.

Most of his books have some aspect of this, twisting the timeline of the narrative, but this one, this moment, is my favorite.

This feels like it's examining the things that Faraway Places left unspoken. Where the family discord only hinted at is now on full display. It's a portrait of small-town America that's both heartbreaking and inspiring. Beautiful and terrifying. It's that moment of change, again—so much of it about that universal feeling, of becoming self-aware, and alienated from where you grew up, and wanting something different, but not knowing what that different thing is. Just knowing you have to find it.

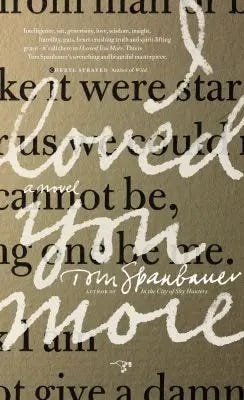

I Loved You More (2014)

We are so fragile.

Ben is a writer from Idaho, studying writing in New York City. He's gay and he's in love with his straight friend Hank, and then Ben is diagnosed with AIDS and moves to Portland, where he falls in love with a woman. And that woman comes between him and Hank. The fallout is messy and embarrassing and it hurts to read. Not just because of how passionately and accurately Tom renders the emotion on display, but because you know there are pieces of him inside this, and you're shocked and in awe of not only how much he's willing to share—to go to that place that hurts—but that he frames it in a way that brings you and your life and your pain into the story.

Ben is an avatar for Tom is an avatar for you.

The really special thing that I Loved You More does is take Tom's playfulness with narrative and upend it. Turn it into something new. Time suddenly has less meaning, and the narrative voice is less living in the moment as much as commenting on the moment. And it produces probably the most personal and reflective book of Tom's career.

Reading this book, after having read all of Tom's other books, and after having sat in his basement, so close to him at the table my knee would knock into his and he would place his hand on my shoulder when making a point, I know that this is where it all comes together. Like the stories he's told since Faraway Places are a tapestry, the threads finally being pulled taught. Revealing the full picture.

No magical realism. No myth or legend. No Chinook winds. Just a man and his life and what it meant to him. The bad parts and the good parts, and what those parts have assembled.

There's this one scene, where Ben and Hank and Hank's girlfriend Olga, they're in an old house, and they've just had dinner, and it's dark, and they're dancing to Billie Holiday singing April in Paris, and I wanted to revisit that scene, because of how strongly it comes back to me. So I opened the book just now and I swear to fucking god, I opened right up to that page, first try, didn't have it marked or anything. Like the scene wanted to be re-read.

So what did I do? I re-read it, and I got that hot feeling in my throat, like I wanted to cry, or just sit back in a chair and read the rest of the book again. It's a small scene, on the grand scale of the book, but it's one of those moments of pure fucking beauty that come along when you don't expect them. You know what I mean? Those moments where all you can do is hold your breath, try to hold it in. Pray that someone writes it down.

That's what Tom does. His writing is a collection of those moments. And his willingness to go to those places of pain makes the moments of beauty stand out that much more.

Thank you for this beautiful piece. Tom has been a major inspiration for me as a human, as a lover, as a storyteller. Only after his death am I learning he was once a Vermont resident…as someone currently living in VT, I’d truly love to find out where. Any clues?

I saw Chuck wrote about his death. I've never read his work & am drawn now. Thanks for sharing